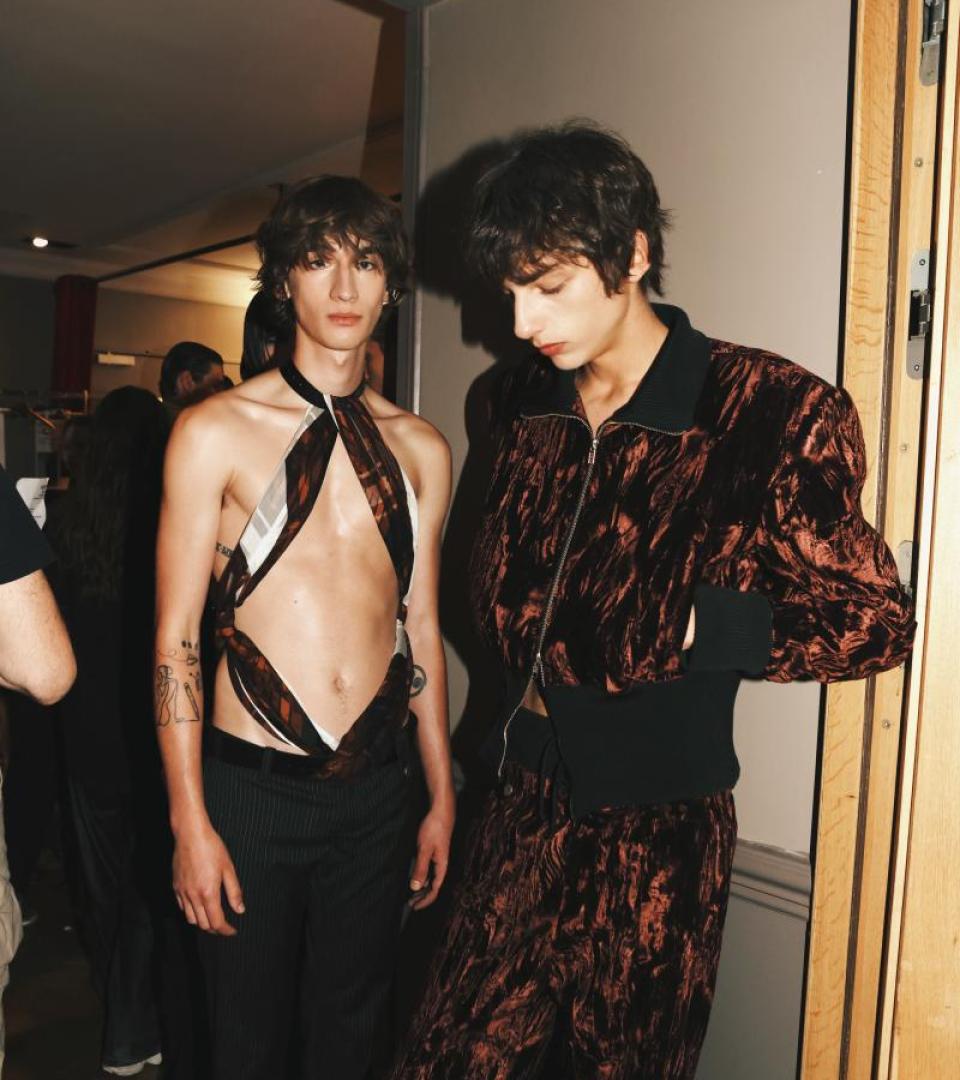

Hands Up: Veronique Leroy

When one visits 32 boulevard Ménilmontant in Paris, one must pass through a gate and walk along a flower-filled alley. An old Buddhist temple has been refurbished as a showroom, a workshop. Boxes, books and magazines fill the room. Véronique Leroy’s twenty-five years of archives testify to the strength of her instincts; the vivacity that has shaped her style and her allure. “I keep everything. I remember every fabric. This is the memory of touch.” So begins this conversation that instantly focuses on the essential: Azzedine Alaïa’s hands.

The hands that she observed for a long time. “These large hands, with well-shaped fingers, always pinning, tidying, cutting.” Véronique Leroy worked as an apprentice in a tailoring school and after more than three years with the master, and from this experience she retained his absolute taste: “I love the hands of the craftsmen.” Those hands are similar to those that belong to her friend and milliner, Elvis Pompillo. “When I see him modeling with his thumbs, I feel like he was born to do it,” she notes. Her father was a worker, and she has kept this mastery from her family: “We have always been more skilled with our hands than with words.” However, her hands are as precise as her silhouettes: carved, constructed, with a distinctive grip. “I don’t like chance. I can play Russian roulette in everyday life. But not in my craft.” More specifically: “In a garment, everything is about support. I like fabrics that allow for architecture, fabrics that have a hand.”

To say that Leroy was influenced by the ready-to-wear of the ’80s is an understatement, as it was precisely this style that took centre stage, expressing power. An attitude. Today, Harris tweed, wool crepe, Japanese denim – all fabrics flow seamlessly under her fingers. She even manages to give volume to a knit without ever making it boxy. Everything remains balanced. The winter of 2022 reveals this tension between the slightly crisp, compact materials in warm, autumnal colors. With her hands underlining the flounces of a skater skirt, clutching an oversized coat, she states: “My anxiety, my impatience, my hands reveal them. They betray me. Sometimes I put on transparent fake nails, but it’s ridiculous, it’s not me. I like them when they are working… What is important is to do – to do again, to know how to stop. Then the work becomes a meditative experience.”