Junko Shimada: “I was so drawn to Paris, to French culture, to its openness and diversity.”

The career of Japanese designer Junko Shimada is a combination of phenomenal creative strength and irrepressible drive for independence. Arriving in Paris in the 1960s, she found herself in the midst of a cultural and social frenzy. She first honed her skills at Mafia, the revolutionary communications agency, then joined Cacharel before launching her own fashion House. Growing alongside the legendary Azzedine Alaïa and Kenzo Takada - for whom Paris was also a welcoming land - she depicts fashion as a profoundly human adventure, a succession of encounters with free, assiduous and passionate spirits.

Her studio is adjacent to her Paris boutique on rue Saint-Florentin. On the racks hang pieces from the new collection, along with animal-head masks on wooden mannequins, an eagle, a frog, a blackbird. “It's for the presentation. It's going to be like a jungle. And it's funny, you have to laugh in fashion, and in life too,” she states with a smile. The collection is conceived and prepared in Paris, and some pieces are produced in her Japanese ateliers, “mainly knitwear”. Shimada makes clothes that are “simple and beautiful, for everyday women. Sexy too, but sexy comes naturally. It's an attitude, it doesn't have to come from the clothes.” With two collections a year since the launch of her House in 1982, Shimada has mastered the art of reinventing herself while remaining deeply faithful to her signature style and values.

“In Japan, I used to spend my time at the cinema watching the films of the Nouvelle Vague. I was fascinated by Paris.”

Fashion wasn't a vocation; it was a key to independence. “My mother found herself raising me alone and I had to get a job. It was difficult to be an independent woman in Japan at that time.” She chose sewing, because “it's a profession, but it was also useful for everyday life. I liked drawing and painting, but you couldn't earn a living that way.” She joined the Sugino Gakuen Dressmaker Institute in Tokyo and spent most of her free time at the cinema, carried away by the Nouvelle Vague and its emblematic figures including Jeanne Moreau, Anna Karina and Jean-Paul Belmondo. This movement redefined French cinema and imagery of Paris, radically overturning traditional codes.

After graduating, and getting engaged, she decided out of the blue to go off on her own to Paris for three months. “I was so attracted to French culture, the music, the cinema, the culture. And everything I had imagined was there. It was fantastic, I was so happy.” She arrived in Paris in 1966, amid an unprecedented social and cultural revolt that would spread shortly afterwards. An eruption of anti-authoritarian, anti-patriarchal, anti-paternal claims, for equality in short, and the freedom of being. And that's precisely what Shimada came here to seek, then to find.

“I went back to Japan and cancelled the engagement. I wanted to settle in Paris.” Not speaking a word of French – “it was very difficult, I couldn't even pronounce the word Mademoiselle” - she landed and set down in Montmartre, without a work visa.

When André Breton, leader of the Surrealists, theorised about “objective chance”, he could have used the meeting of Shimada and Kenzo Takada at the bank as a convincing example. One of those chance meetings, like two creative compatriots who spontaneously act like magnets to one another. “He was a kind, intelligent and very generous man. He spoke a worst French than mine! I told him I was looking for a job to stay in Paris and he helped me.” Thanks to him, she worked for a few months at Relations Textiles, the very first trends office launched in 1957 by Claude de Coux, for whom Kenzo himself worked before launching his own brand, Jungle Jap, in 1970. “He was fun, we went out every night. He even fell in love with my Parisian fiancé at the time.”

“I saw two women get out of a Porsche with extraordinary attitude. It was Maïmé Arnodin and Denise Fayolle, from Mafia. They looked like the women of the Nouvelle Vague.”

She met Kenzo Takada at the bank, and the founders of Mafia coming out of a bakery, thumbing her nose at all the cynics who still roll their eyes when hearing clichés like “Paris is a village”. “I saw a Porsche hurtle towards me and stop at the last moment. Maïmé and Denise had incredible strengths of character.” She followed them with her eyes, not really knowing who she had just met, but eventually realised that it was the famous “mafia” that her partner at the time, an advertising agent, used to talk about. “I went there without an appointment. I waited but I ended up meeting them. I wanted to work there.” And they gave her a test: lingerie. “I'd never done that before, so I gave it a go. I said to myself that we use silk or nylon all the time for lingerie, so I wanted to have some fun by proposing a concept of pieces made entirely from towels.” She drew up, and the idea went through. She remembers the offices, “the white floor, the white walls, the white table, just one red spot, the telephone,” and a line of women, all women. “It reminded me of Takarazuka, the all-female Japanese theatre. And what beautiful women! I understood afterwards.”

Fashion appealed to her; she designed it, conceived it, but hadn't made it yet. In 1970, on Maïmé's recommendation, she joined Cacharel to take over the children's line, then the men's line and the “Fikipsi” line, the House's sister brand. Cacharel, founded in 1958 by the former mayor of Nîmes, was enjoying its glory days at the time. Cacharel became an experimental laboratory for creative virtuosos, including Agnès b., Emmanuelle Khanh, Dawei Sun and Azzedine Alaïa. “Azzedine was so funny, and a wonderful cook. He would do the sewing on the table, then we'd tidy up, put a tablecloth on the same table and have dinner with friends every night. Thierry Mugler was there too, in the early years.” She remembers the creative genius: “He had an extraordinary technique. As soon as he touched the fabric, the volume changed.” Shimada stayed with Cacharel for seven years, working during the day and enjoying the bustle of the Rue Sainte-Anne in the evenings, where the whole of Paris met. “I loved it, I was happy. I came here to discover the difference, the diversity. I didn't want to end up eating rice and seaweed every night, I wanted something different.”

“For my first show, I only used striped men's shirts to make a very tailored suit, a lined trench coat, a pencil skirt...”

The day she left Cacharel, she received a call from a Japanese financing company. “They wanted us to work together. I didn't know what I wanted to do, so I asked for a year to think it over.” When she returned, she felt ready and the Junko Shimada company was created in 1982. “It was a great vote of confidence and I'm very grateful. I told them my story and they answered me that everyone came to see them to ask for work, whereas all I could talk about was love.”

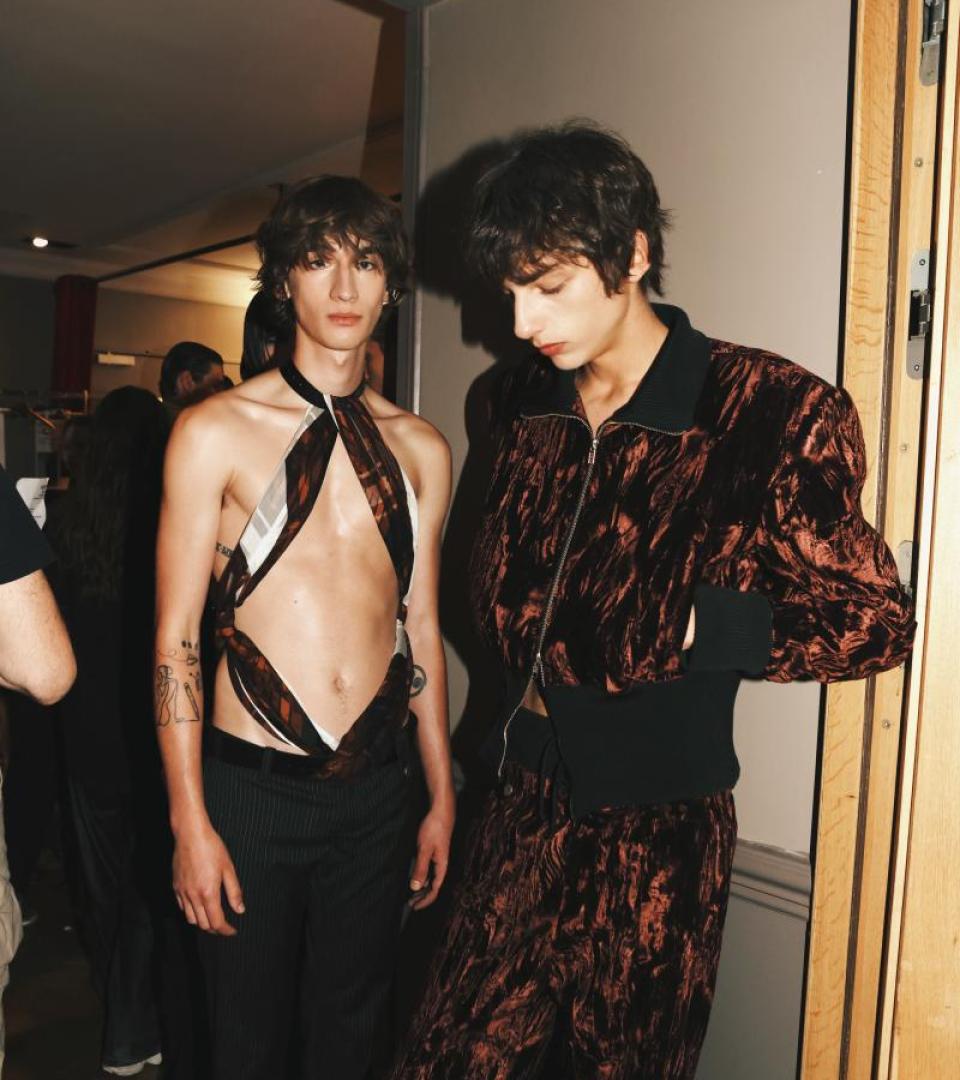

Five people from her team at Cacharel followed her, the project was launched, and her first fashion show was held at the Pavillon Gabriel in Paris. The entire collection was made from men's shirts. “Poplin and striped cottons were so sexy. The Japanese were worried that it wouldn't sell, but the French press helped me a lot.” It was at this point that she found herself referred to as “the most Parisian of Japanese designers”, a term that would never leave her. “At that time, we had around forty models wearing two or three outfits per show... There were many, many models. Now we do a lot less, presenting between 25 and 30 looks per season.”

She remembers “the dresses we finished at the last second, or that we could create in a few minutes once the show had started. One season, I even did a show of wedding dresses only, rather than just one for the last silhouette.” Shimada opened her first boutique on rue Etienne Marcel in Paris in 1984. A second Parisian boutique was opened on rue Saint Florentin in 2001, where she now presents her collections. In 2020, she confirmed national recognition when designing the Japanese team's suits for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games, under her “Junko Shimada JS Homme” licence.

“I go back to Japan two or three times a year, because I don't want to uproot myself. I left this country and separated from the father of my daughter, whom I raised alone. Like my mother, who raised me alone. She's the one who gave me this idea of independence.” Junko Shimada is an unstoppable, indomitable force of character who has never stopped enjoying life with the utmost rigour. Of these seemingly lighthearted creative professions that we approach with absolute seriousness, and glee.

Reuben Attia.