Jenke Ahmed Tailly: “Fashion has the incredible power to bring cultures and communities together.”

Jenke Ahmed Tailly, stylist and artistic director, offers a deeply human approach to fashion that unites the diversity of beauties. From his first steps in Côte d'Ivoire, cradled by traditions and ancestral know-how, to his prestigious collaborations with established houses and emerging designers, and his unrivalled work with icons such as Isabelle Adjani, Beyoncé and Naomi Campbell, he has turned his roots into the driving force behind a creative and inclusive philosophy.

The fashion industry is a complex maze of often little-known professions. The stylist, a behind-the-scenes job, is the person who assembles clothes and invents new ways of wearing them. For fashion magazines, social media, videoclips or publicity campaigns, they bring characters to life and invent images that change our perceptions of beauty. “I want my work to speak to the women and men I love, whatever their origin or skin colour. I want to show the multicultural world in which I grew up in Abidjan, with so many different nationalities. I was sometimes in the minority at school in my own country, and I thought that was fabulous.” Tailly grew up in “the first Senegalese family to emigrate from Senegal to Côte d'Ivoire.” When he was very young, his parents separated, and his father remarried in France. “I spent my school year in Abidjan and most of my school holidays in Paris. I've always been attracted to things that are different from me.” A contagious enthusiasm, a resounding personal style that would make the quiet luxury crowd swoon, and a deep, transcendental need to pass on his heritage: his career is a treasure chest of anecdotes and life lessons.

“I didn't know that fashion could be a profession.”

From an early age, Tailly understood that a garment, a practical everyday object, may harbour a profound symbolic value. “For all the great African families, traditional ceremonies mark the stages in a human being's lifespan. For each occasion or event, there is a symbolic garment, specific fabrics. For the Wolof tribe in Senegal, for example, christenings require white lace called borodeh. Each tribe has its own particularity in terms of thread, design and techniques.” This is how he discovers fabrics and know-how, and learned without realising it. “Every week, my aunts, my mother and my grandmothers had to make outfits. Instead of going out to play football, I would stay with them and advise them. I learned to recognise real silk, taffeta, alpaca, guipure, Kente, which is a traditional fabric... I'm thinking of the Baoulé loincloth, which is very similar to the Ndiago loincloth from Senegal.” This is precisely the expert consulting he would go on to practice for the rest of his career, as though he was learning his craft from those closest to him before taking the plunge.

“I used to read a lot of my mother's magazines, ELLE, Vogue... My mother loved fashion. She could wear a boubou on Monday and Saint Laurent on Tuesday.”

As soon as he could be independent, he packed his bags and flew to New York. He studied marketing and at the same time discovered fashion as a model. “That's when I discovered the different professions behind a fashion image, from production to lighting and set design. I realised that fashion is like cinema: it's a whole team telling a story.” Unsure of his path, he had a feeling that fashion was attracting him and was looking for his place in it. He discovered retail as a sales assistant at Barneys and Bergdorf Goodman: “I was already very familiar with the French fashion houses, but I discovered a lot of American brands and how a fashion boutique works.” After graduating, he briefly joined Donna Karan but eventually returned to Paris to work for Benetton. “I became the youngest marketing and merchandising director. One day, I arrived at a shooting and fell in love with the job of stylist; it was a revelation. I didn't say anything to my parents and resigned from one day to the next. I called a friend, Miles Cockfield, fashion director of Berliner Magazine, because I wanted to assist him. I'd found my calling. He immediately offered me a job as fashion editor.”

Finally settled into his shoes, the adventure began, and Tailly jumped in with both feet. For his first shoot as a stylist, he worked flat out. “The theme was the trench coat. It was a delight to immerse myself in the history of the garment, from Thomas Burberry who created it in 1914, to Yohji Yamamoto and Comme des Garçons who deconstructed it, to Rodarte who romanticised it.” Above all, Tailly can't imagine his first publication without Alaïa. “My mother adored Alaïa and I absolutely wanted to have a piece. He contacted the press teams, went to the showroom and met Mr Azzedine Alaïa himself. “I was in the boutique the week before with my mother, and I think he recognised me. I explained the project to him and he replied: ‘We don't have any trench coats in the latest collection, but if you'll follow me, I'll lend you some from my archives.’”

When Tailly talks about Azzedine Alaïa, his eyes glaze over and his fists clench. “He was my adoptive father. He's no longer here, but he's in my prayers every day.” Tailly remembers his exceptional generosity. “He always supported me. A week after that first shoot, he organised a dinner and introduced me to the titans, the major figures of the industry, such as Franca and Carla Sozzani and Farida Khelfa. I never allowed myself to call him by his first name, even when he insisted. When a legend gives you so much love, you sometimes wonder what you're doing there, if you deserve it. I have a lot of very intense, very touching memories. He always had people over to his house. He was in the kitchen, serving and seasoning. He was a master of ceremonies.”

It was while working with Mr. Alaïa that he met “the great Sophie Theallet,” the designer's right-hand woman for over ten years. She then moved to New York to launch her own House in 2007. In September 2015, she presented a collection in homage to Africa, alongside Tailly. “I'm very proud of it. We found this rooftop that reminded us of the Médine district in Dakar, Senegal. We brought in the drums of Doudou N'diaye Rose's troupe, who had performed at the bicentenary of the French Revolution under the artistic direction of Jean-Paul Goude. It was beautiful, captivating, joyful. Absolutely chic, a celebration... A very high point in my career.” Theallet remains the only French designer to have won the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund award, in 2009. At the time, journalist Cathy Horyn described her in The New York Times as “the real deal, a designer who knows how to make clothes from start to finish.”

“I've created my own freedom, and I've always fought for diversity wherever I've worked.”

Fashion images shape and freeze our aesthetic references, imposing themselves as cultural benchmarks. By recognising African heritage and giving it pride of place, fashion becomes a vehicle for authentic, plural representation. Tailly’s career has been marked by three major magazine covers.

In 2011, his reputation skyrocketed when he signed the cover of the 90th anniversary of L'Officiel. “When I did my research, I realised that in 90 years, there had been less than ten black girls on the cover. To represent 90 years of fashion, I immediately thought of Beyoncé. She's absolute royalty, her presence, her aura, beyond her vocal abilities, it was an obvious choice.” With just a few phone calls, Beyoncé heard about this outgoing young man with contagious enthusiasm, and the project became a reality a few months later. “All the fashion houses I contacted had prepared made-to-measure clothes for Beyoncé. For the fittings, I arranged the room as if we were entering African royalty. I borrowed works of art, even a piece from the Quai Branly. Fashion is very much inspired by Africa, and with my heritage, I can look at any collection and find an African inspiration. It was a wonderful exercise for me.” For the cover, he chose a Gucci piece by Frida Giannini, creative director of the House from 2006 to 2015. “She put out an incredible collection inspired by Saint Laurent's 1967 African collection. It featured codes from the Bantu peoples, pieces with conical breasts, Bambara breasts. This is the name of a Malian community whose female statues have very long bodies and pointed breasts. The conical breasts are often attributed to Jean Paul Gaultier, but it was Yves Saint Laurent who first introduced them in Paris.” Tailly has worked with Beyoncé for several years, most notably in 2013 for the iconic Super Bowl performance. “I'm one of the only Africans to have been the artistic director of the Super Bowl,” he recalls. He also followed her to Cape Town in 2018, when she gave a concert to celebrate Nelson Mandela's 100th birthday. He even introduced her to Mr Alaïa: “He really enjoyed the song “Single Ladies”, and it became a ritual to listen to it during fittings with the cab models. He was really happy to meet her.”

“I had the honour of working with Beyoncé, Kim Kardashian, Iman Bowie, Natalia Vodianova… My ultimate dream was to work with Naomi Campbell.”

“Naomi is one of the most beautiful people I've met.” Their collaboration has resulted in some phenomenal fashion images. In November 2018, they signed a resounding cover for Vogue Arabia. “I wanted Naomi to wear afro hair. It's nice to do the flip side, to present something new. In the end it was a huge success. And I mixed up the looks, I took a pair of trousers and made a top out of them, I reversed the pieces, I had a blast.” Also, in March 2021, Madame Figaro presents “L'Odyssée de Naomi”, an issue entirely dedicated to Naomi Campbell, under Tailly’s artistic direction. “We had a 100% African team, from Ghana, Cape Verde, Senegal and Nigeria. It was magnificent. We chose an outfit by Olivier Rousteing for the cover.”

Along with Naomi, Tailly is committed to identifying and supporting emerging African talent. Together, they chaperone Arise Fashion Week in Lagos, Nigeria, which since its launch in 2007 has become one of the major continental references for African designers. Together, they draw the Western fashion spotlight on the continent's most promising talents and exceptional know-how. “Naomi and team were the first to invite André Leon Talley to Africa. When he arrived in Nigeria, he was amazed by the beauty of what he saw. He was also able to meet Reni Folawiyo, founder of Alara, one of the most beautiful concept stores in the world. It hosts the biggest European fashion houses alongside the most creative African designers.”

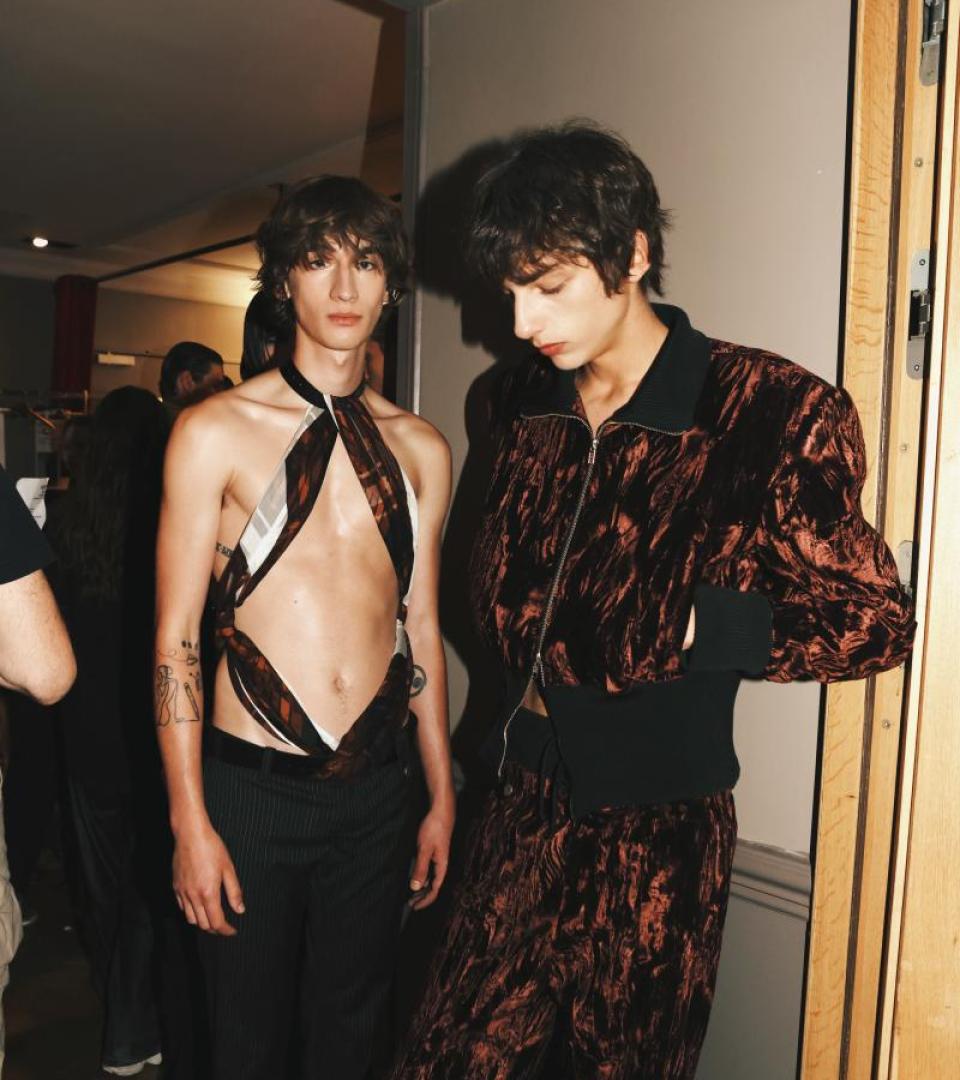

It was there that he discovered the brand founded by Adeju Thompson, Lagos Space Programme, now on the Official Calendar of Paris Fashion Week. “During the pandemic, Naomi and team organised a competition. The designer Kenneth Ize won and Lagos Space Programme was one of the finalists. We saw them arrive. When they entered the Paris Calendar, they asked me to go with them, and I was delighted to help.”

Tailly also works with the CANEX (Creative Africa Nexus) initiative. In September 2024, during Paris Fashion Week, more than 18 fashion brands from all over Africa and its diaspora presented their creations to the professionals in attendance. The space showcased a wide range of brands including Mafi from Ethiopia, Adele Dejak from Kenya, We Are NBO and Katush, Doreen Mashika from Zanzibar and Emmy Kasbit, Wuman and Bloke from Nigeria. South Africa was represented by Judy Sanderson, David Tlale and Thebe Magugu, while Zimbabwe was represented by Vanhu Vamwe.

“Working for Chanel was my dream. The House represents French savoir-faire and French elegance.”

On Tuesday 6 December 2022, Chanel presented its Métiers d'art show in Dakar, Senegal, becoming the first luxury brand to unveil a collection in sub-Saharan Africa. “They told me about this project three years before and we started work a year before the show. It was my dream. It's the most chic French fashion House. I've collaborated with the House for a long time and it's one of the most loyal Houses I've ever worked with.” Tailly is still very moved that a French fashion House, such an established reference for absolute elegance on a global scale, has decided to bring Senegalese savoir-faire to the forefront. “It was extraordinary. Everything was done by Senegalese teams. Even the notaries who prepared the contracts were Senegalese. I introduced them to the local equivalent of 19M, the Manufactures sénégalaises des arts décoratifs (MSAD) in Thiès, set up in 1966 on the initiative of former president Léopold Sédar Senghor.”

“When I work, I sometimes have the impression that it's not my hands. I think that what I do in fashion is sacred, that it doesn't even come from me. It's like I'm being carried by my ancestors.”

“We don't have a written tradition. Every African family has a “griot.” It's a repository of oral tradition, a transmitter of memory. They hold the book and know who your ancestors were.” When young Tailly lost his mother, he travelled to Africa to immerse himself in his family history. “My father comes from a royal African family, from Baibli in the west of Côte d'Ivoire, and my mother comes from a highly spiritual line. I think that what I do in fashion is sacred and that it doesn't even come from me. I think that, when I'm in my element, when I start working, it's as if it were another hand, as if my hand was carried by my family. It's an ancestral heritage that I'm starting to really understand today.”

“In fashion, despite everything we do, we start from scratch every season. It's a race, and even if you come in first one time, you're right back at the starting line.” After all these years of learning the ropes, immersing himself in so many House worlds, so many designers' visions, he feels ready. “It's time for me to launch my own brand. I've been working on this project for a very long time.” In a few seasons - Tailly is a playful creature who masters the art of suspense like no one else - he will present a collection of coats in Paris. “Coats don't exist in Africa and that's why I've always been fascinated by them. In Abidjan, when it rained, I was the only one to come in a mackintosh and the others didn't understand, but I remained proud. The coat is protection, it's what wraps you up.” Paying homage to his heritage through Western clothing remains his lifelong struggle, which he is now fully embracing: recreating new models, new images, new symbols.

Reuben Attia