Frida Kahlo, Beyond Appearances

Filling nearly the entire Palais Galliera in Paris, Frida Kahlo, Beyond Appearances is a vast exhibition that explores the visionary Mexican artist from multiple illuminating and intimate perspectives. Shifting the focus from her body of work, the 200 objects on display – including her vibrant wardrobe, striking footwear and jewellery, miscellaneous items like old makeup, orthopaedic aids, and correspondence – reveals how she constructed and upheld an image that was inextricably linked to her art, her politics, and her disability. This collection was secretly held by her husband, the artist Diego Rivera, at their home in Casa Azul, only to be discovered 50 years after her death in 2004. The exhibition also features a captivating selection of photos – from familial to professional – taken over her lifetime that illustrate how she used portraiture to reflect and deflect from reality. As a natural extension of the show, the Palais Galliera has dedicated its upper gallery to contemporary fashion and the designers – Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel, Riccardo Tisci, Jean Paul Gaultier, Alexander McQueen and Yohji Yamamoto among others – who have drawn inspiration from her inimitable style. “Kahlo was enigmatic, mysterious and beautiful,” says Circé Henestrosa, the curator and designer of the exhibition, who is Head of the School of Fashion of Lasalle College of the Arts, Singapore. Here, she shares additional insights – and a personal anecdote – on a dazzling presentation of what remains of the artist beyond her art.

Frida Kahlo took a subversive approach to her art — whether deliberately or not. How do you see this extending to her style?

I think everything Kahlo did was deliberate. The way she dressed and the way she painted. She was able to break a lot of taboos about women’s experiences, about the challenges to overcome illness and physical injury, both exposing them and working through this trauma in creative ways, that she portrayed through her art and dress. This resilience, her fighting attitude, and her determination to enjoy life despite the difficulties she encountered make her a powerful symbol as she continues to speak to many different groups. Her iconic image communicates strength and the possibility for change.

Kahlo developed a certain ease in front of the camera thanks to her father that continued through her life despite her disability and illnesses. Was she determined to present a different self through these images?

Yes, Gannit Ankori our advising curator pointed this out to us. She highlighted the close relationship between Kahlo and her father, and we observed how Kahlo started becoming very conscious about her body and the way she posed for photographs. As soon as she could sit up, her father cultivated her predilection to perform in front of the camera. Also, Kahlo’s mode of posing for photographs strongly impacted her painting too. Her intense, gaze and the slight turn of her head appear in photographs and paintings alike. Furthermore, the meticulous care with which she fashioned her style parallels the fastidious way she composed her paintings during the prime of her life.

In the photos when she is traveling outside of Mexico, she continues to wear traditional garments, even when incorporating a more “European” dress. Why was this important to her?

I think she understood the power of clothes as a vehicle to communicate the different messages she wanted to convey. Her political beliefs, her gender identity and her Mexicanidad [“the essence of the Mexican”]. She had a mixed heritage; her father was German and her mother was Mexican and the wardrobe is composed of mixed pieces too. Her wardrobe is mostly composed of traditional Mexican pieces from Oaxaca and beyond… Among all her clothes, though, it was the Tehuana dress that Kahlo chose as her signature style. In her wardrobe, there are sixteen Tehuana blouses and twenty-five original Tehuana skirts some of them sewn and personalized by Frida. She created a hybrid style.

There are several portraits taken by female photographers and then then the series by Nickolas Muray. Do you detect any differences between a female and a male gaze across these photos?

Kahlo was photographed at her home, the Casa Azul, where she spent increasingly more time, due to her deteriorating health. Lola Álvarez Bravo and Gisèle Freund took some of her most intimate portraits, which are shown in the exhibition.

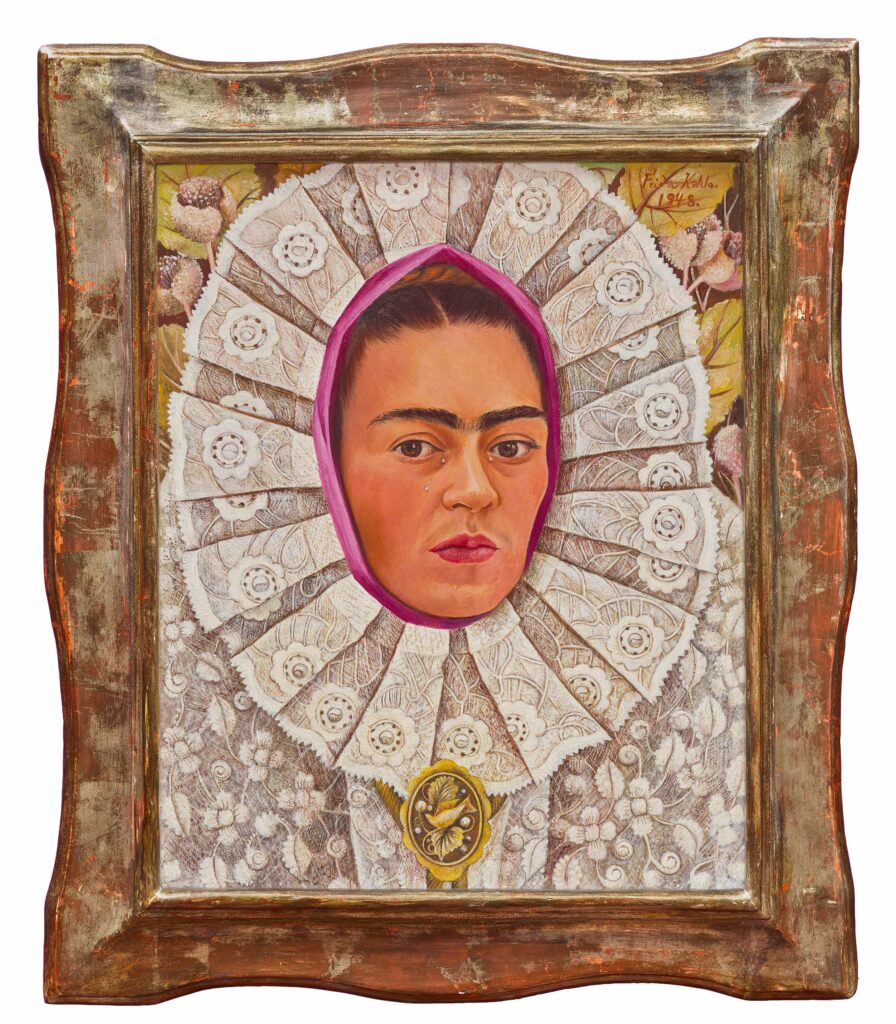

In 1931, Frida Kahlo met the Hungarian-born US photographer Nickolas Muray in Mexico. Muray pioneered colour photography in the US during the 1930s, having travelled across Europe learning about colour processes and print techniques. Over a decade, Muray and Kahlo collaborated to make wonderfully vivid images, with sitter and photographer equally active in their composition and framing.

The resulting portraits of Kahlo are some of the most dramatic and memorable ever made. In many, she wears her favourite – and flattering – magenta rebozo, mentioned in her letter to Muray of 13 June 1939. These images reveal the way Frida composed her outfits and the care she took with her colour palette, matching her rebozo to the flowers in her hair, and coordinating her use of lipstick and nail varnish. Muray, meanwhile, was able to draw on his experience as a fashion photographer for magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, TIME, and Vanity Fair. He said, “Colour calls for a new way of looking at people, at things”.

Which aspects of her style and wardrobe choices stand out strongest to you?

My favourite pieces are of course the Tehuana dresses for my connection with that dress. I grew up hearing stories of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. My father’s family came from Tehuantepec, in the southeast of Mexico, and my great-uncle Andres and great-aunt Alfa moved in the same circles as the famed intellectual couple in the 1930s and ’40s. Alfa, my great aunt gave Kahlo her first Tehuana dresses – the full-skirted, embroidered gowns worn by indigenous women in Tehuantepec – which Kahlo later adopted as her trademark. So, I wanted to know why Kahlo had adopted this look as her logo, and I was interested in the ethnicity and disability aspect of the wardrobe and where they met. From the disability aspects of the wardrobe, I think her prosthetic leg is incredibly modern and beautiful.

Her prosthetic leg is one of the most intricate objects in Kahlo’s collection. Frida Kahlo had her leg amputated in 1953. To hide the leg, she had boots made of luxurious red leather decorated with bows and pieces of silk embroidered with Chinese dragon motifs and decorative little bells. She turned her prosthetic leg into an avant-garde object, an accessory that she adopted as an extension of her body. She did this 45 years before Alexander McQueen took double amputee paralympic Aimee Mullins walking the runway in a pair of wooden carved prosthetic legs he made for her in his Spring-Summer 1999 collection.

Can you elaborate on her impulse to modify some of her orthopaedic corsets with art? Was this a form of self-expression? Of resistance? Of exploring an alternate medium?

Kahlo decorated and adorned her corsets and transformed these medical corsets into items of great beauty. She included them in the construction of her looks as an essential piece and as her second skin. Kahlo also constructed her paintings – integrating her corsets, her costumes, and her photographs into the compositions.

In the contemporary galleries, we see various interpretations of Kahlo’s style and her dress — in many cases, the references are easily identifiable. Would it be fair to say her style is among the most recognisable of female artists in the 20th century?

Yes definitely! As previously mentioned, Kahlo constructed her paintings – by integrating her corsets, her costumes, and photographs into the compositions. Her art and dress are very much linked with each other, and her approach is very unique.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Frida Kahlo, Beyond Appearances continues runs until March 5th at the Palais Galliera in Paris.