Kiko Kostadinov’s Ideological Musings

As one of fashion’s foremost innovators, Kiko Kostadinov is a designer who expertly intertwines making clothes with ideology. Spring Summer 2023 is no exception. Across tailoring and decoration, the Bulgarian designer explores his heritage through the conduit of Zlatyu Boyadzhiev’s paintings that depict rural life and expressive portraiture while referencing Danish-based Vietnamese artist Danh Võ’s tales of collective history and personal experience during periods of war.

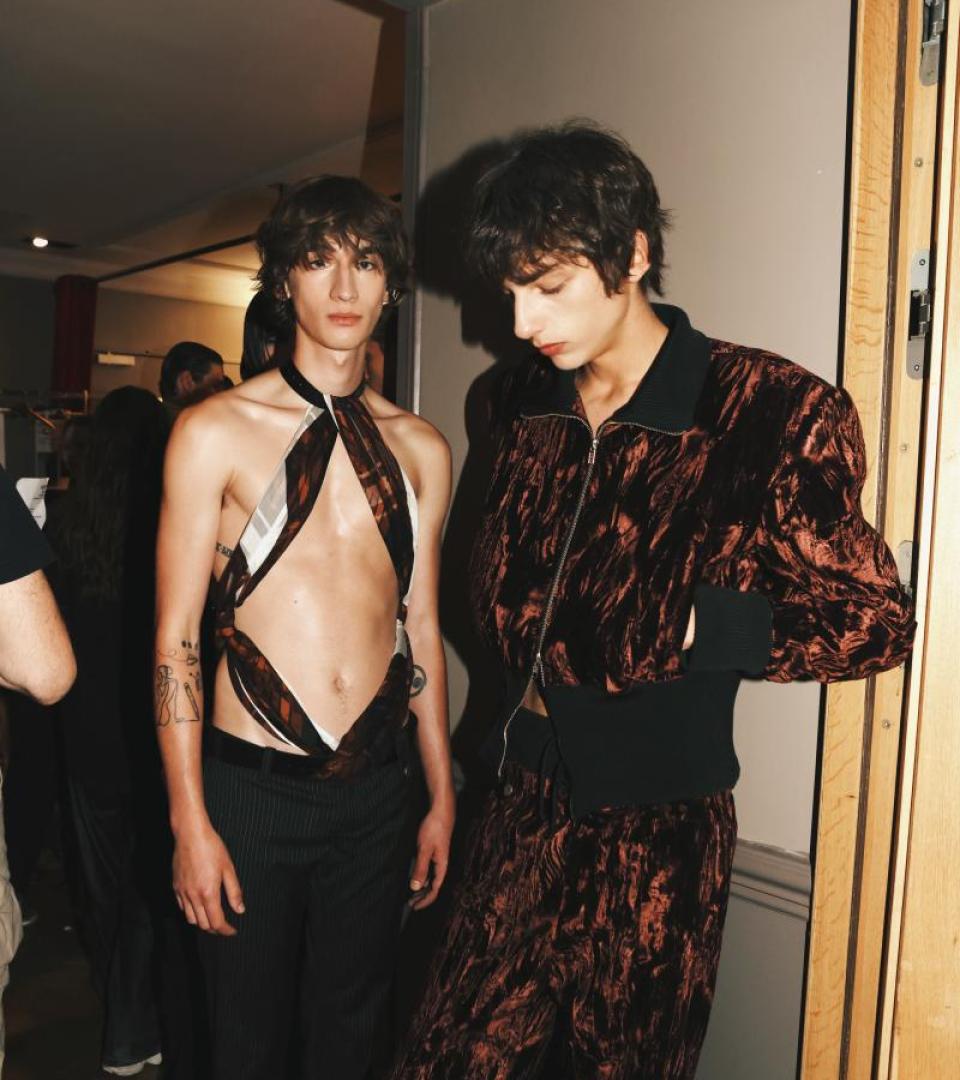

Before settling in London, Kostadinov grew up in a country once ruled by the Ottoman Empire for almost 500 years. This has prompted considerations of how cultural exchanges supersede the differences that divide at a time when cultural conflicts are rife. The past and present communicate in the collection: opening with minimal yet rigorous reversible tailoring in beige, it gives way to overstyled outfits, drapery and details inspired by Ottoman Empire decoration in iridescent and metallic shades and dazzling embellishment.

In the final stages of show preparation, Kostadinov explained that “the challenge and the point of when you’re referencing history is how you make it more contemporary.”

What kind of exploring do you undertake before starting a new collection?

The collection is like a diary of the past six months. Of course, not necessary just those six months because some of the research can trigger looking back five years, 10 years, or 100 years. The foundation is based on those six months and wherever it takes me that’s added to the conversation. I don’t just sit and think, “let’s pick this book” or “that’s cool, let’s pick this and make a storyboard.” It comes at a time when I don’t think about the current season. Like now is a good period because I’ve just finished the season and my mind is opening up and waiting for the next touch of direction of where to go.

Some designers talk of exploring the world around them — places, culture, issues; while others explore internally — feelings and responses. Tell us what comes more naturally to you?

I set myself boundaries and things that I don’t want to be referenced. For example, I always struggle to reference a subculture. I find it difficult to connect to something in the past. There’s this nostalgia for something that happened, like, 50 years ago and it’s been reproduced so much especially through a fashion context. In the past few years, it’s been very hard referencing different cultures because you need more context. Even for me, it was hard. In the past two or three years, I am more open to referencing my own culture like where I come from in Bulgaria. That’s been quite exciting because I didn’t want to start with that in the beginning. Even in school, I never really referenced any of that, because a lot of other students were always like, “Oh, I come from there. This is traditional dress,” or “This is what my grandmother used to wear.” I’m having a different relationship with my country. I was not planning on going back in any capacity when I was at university, I wanted to forget about it and focus on what’s in front of me. But the older I get, producing the clothes and going back more often and having these flashbacks of my childhood helps introduce some aspects and research for something that I knew when I was in school, but never really as an adult. So it feels new.

Do you think you’ve become more sentimental about this aspect of your heritage as you’ve gotten older?

I don’t think I’m sentimental about anything. It’s just part of the process and I don’t know how long it will be; it could become a core part of the brand, or I might feel like in a season or two, I go back to the old way of life. I might want to look at something more futuristic or modern. It’s very obvious that we don’t need more fashion shows or production so I’m thinking what can I bring from within my upbringing and where I come from and put a twist on it that you can’t really find in someone else’s work. But again, that’s a big question because you can buy another pair of trousers, it’s not like we’re doing something special that nobody makes. It’s having the confidence about colour combinations, stitching, details, shapes of clothing – it’s a personal journey. That’s why we change every season rather than remaking the story in different colours.

What kind of ideas and references are you drawn to this season?

There are some core ideas but I found them more for context rather than for visual references. I really like the work of Vietnamese artist Danh Võ and his recent showing at White Cube and Marian Goodman Gallery. It’s woodwork made from wood from [former U.S. Secretary of Defence during the Vietnam War] Robert McNamara’s son. It’s this strange relationship and I love how he uses it instead of having anger towards, let’s say, the Vietnam War. I’m not sure because I don’t know, I haven’t spoken to him. But I always find it very fascinating. He talks about fallen empires which, to me, has always been the Ottoman Empire. It’s a big part of where I come from. I’ve been told about it from a very early age, how awful it was, and how you need to be super patriotic and super proud. I think there’s resentment – even propaganda – towards Turkey. It was interesting for me to not feel this way and just embrace [the relationship]. It’s more of a personal dialogue rather than making some kind of point.