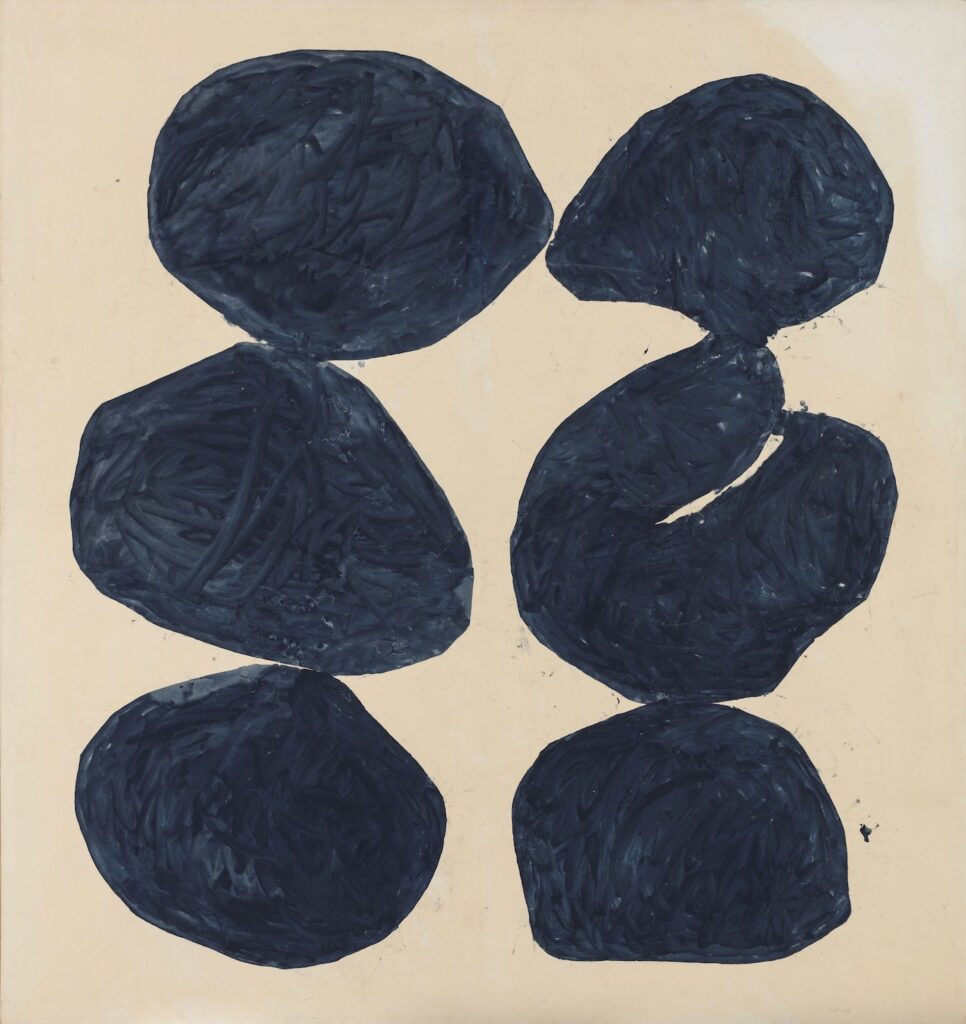

Simon Hantaï: A technique mastered

Anne Baldessari, curator of the centenary exhibition of Simon Hantaï (1922-2008), currently on at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, shares insight on the distinctive and radical folding methods that the Hungarian-born abstract painter explored and expanded upon throughout his career. The process by which he transformed material dimensionality to a stretched canvas might seem like the inverse of clothing construction that begins as a pattern or a flat piece of cloth only to be rendered with volume. But Baldassari, a French heritage officer, notes that Hantaï was never thinking in these terms and why a collection inspired by his Tabulas would be a superficial interpretation of the artist’s systematic approach.

- Our theme this season is exploration. How unique is it to see an artist explore one method over his entire career?

One can consider that the research question is at the heart of the modernist approach since the beginning of the 20th century. But it is rare that a new technical procedure truly revolutionizes our understanding of art. Hantaï discovered “folding” in 1950 and it took him ten years to develop a “method” and never stopped exploring its plastic, ethical and philosophical potential.

- Folding, or pliage, introduces a dimensional aspect to a canvas, but Hantaï would then smooth out the pleats and stretch the canvas flat, eliminating the ‘reliefs.’ Was his intention more about process or outcome?

Hantaï makes the folding method his own and applies it, reinventing it in each of his series, as an absolute necessity: carried out blindly, the eye floating, the folding (whatever its form: pleating, crumpling, crushing, knotting…) is the product of an automatic hand. The staining of the fabric once folded is also done automatically. The effects of reliefs, sharpness, and all dimensional traces produced by the work of the folding are, for the painter, of a parasitic phenomenon that is necessary to evacuate. Once accomplished by the folding, the painting must ignore these phenomena. Hantaï calls it “uncooking” the painting. He recommends stretching his canvases on a frame and erasing all traces of them.

- There seems a similarity to the way Hantaï folded canvas and the technique of tie-dye (including traditional Japanese treatments as well). Did he ever refer to this himself?

Hantaï never explicitly referred to it. However, we can consider that these techniques of knotting, folding and dyeing were in fashion in the ’70s. What I can recall in this regard is that no plastic technique from the common culture was irrelevant to him. In various statements, he claimed to be interested in the vernacular techniques and procedures of the Hungarian rural culture in which he was raised. For him, they embodied the collective creativity that permeated secular social life and its expressions with meaning and symbolism.

![Simon Hantaï, Tabula, [Paris], 1980Acrylique sur toile295 × 466 cmCollection particulière© Archives Simon Hantaï / ADAGP, Paris 2022 © Fondation Louis Vuitton / David Bordes](/sites/default/files/news/img/simon_hantai_tabula_paris_1980-1024x645.jpg)

- From afar, the canvases suggest repetition but up close, it becomes clear that the ‘grid’ is composed of discrete units. Do you think it was important for him to create a distinction from more of a printmaking technique?

For Hantaï, repetition and difference must equally take part in the painting process. This question is philosophical and exceeds the principle of simple mechanical reproduction. The rule is ensured by the relative metric of the knotting done at more or less equal intervals. Hantaï is a great reader of contemporary philosophy and Gilles Deleuze’s thought in “Difference and Repetition” (1968) was a central reference for him at the time of the elaboration of Tabulas.

- When Hantaï shifts from monochromatic to polychrome, the energy or feeling around the work seems to change. How would you describe it?

Hantaï oscillates between monochromy and polychromy throughout his work. The colour is not specific or symbolic but programmatic. The room dedicated in the exhibition to the large Tabulas allows us to measure this systematic aspect opposed to any decorative reading. Hantaï seems to apply the Picasso rule: “When I don’t have blue, I use red”… The colour is the object of a non-choice, of a deliberate chance.

- Towards the end, there is a room where we see the canvases unframed. What stands out to you here?

In this room, I wanted to evoke rather than reconstruct Hantaï’s “last studio”. This is the place where, from 1982 onwards, he retreated and continued alone and without any other witnesses than a few close friends, a work “in the dark”. At home, in this studio that was photographed by his friend Édouard Boubat, the quilting on the walls was incredibly dense. Dozens of paintings were superimposed as they were being painted. This centennial exhibition thus has four layers of superimposed foldings: buds, old paintings, star folds, dripped folds, domestic folds, prepared folds, etc. One can see the proliferation and richness of Hantaïan research still in progress, and all the more free now that the painter had decided not to submit to diktats of the market or the museum.

![Simon Hantaï, Tabula, [Paris], 1980Acrylique sur toile297 x 266 cmCollection particulière© Archives Simon Hantaï / ADAGP, Paris 2022 © Fondation Louis Vuitton / David Bordes](/sites/default/files/news/img/simon_hantai_tabula_paris_1980-2-926x1024.jpg)

- Designers will always draw inspiration from artists and increasingly, it seems Maisons are entering into direct collaborations with artist estates. What would you think of a Hantaï collection?

A collection of Hantaï designs would be a misinterpretation in my opinion. His work has often been plundered and counterfeited, but in ignorance of its deeper meaning. What is copied, borrowed and reproduced is the visual result, the trace, the effect. But it is the link between the process and the trace that makes the work. With Hantaï, it is a question of “thinking in painting” and not of producing patterns or motifs. The Hantaï Estate ensures that the painter’s work and his purpose are not distorted for commercial purposes.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Simon Hantaï The Centennary Exhibition continues at the Fondation Louis Vuitton until August 29, 2022.