“Haute couture has reached a new golden age.” - Salomé Dudemaine, fashion historian and co-founder of the magazine Griffé

A graduate of the École du Louvre, Salomé Dudemaine is a quite unusual kind of historian. Where some confine themselves to the major fashion houses and the gilded catwalks, she opted to delve into the margins, where light scarcely reaches. Her specialty? The beginnings of luxury ready-to-wear, where the history of fashion in France tends to focus on the great couturiers.

In 2020, together with vintage expert Julien Sanders, she co-founded the magazine Griffé, which tells the story of fashion in a new way, by exploring what goes on behind the scenes and its forgotten players. In short, it's a collective story in which every link in the chain, from the designer to the craftsman, plays its part in writing the greater picture, with the latest issue focusing on the house of Kenzo. Here, she looks back at the major turning points in Haute Couture history and explains how the contemporary scene is shaping what will soon appear to be a new golden age.

How would you sum up the history of Haute Couture? What have been its major turning points?

Salomé Dudemaine : We can identify three great golden ages of Haute Couture, which, as a reminder, is a legal appellation stemming from a 1945 decree and specific to the Parisian scene. While Haute Couture was born in the second half of the 19th century, its first golden age came in the 1930s. It was a period of abundance, marked by a large number of fashion houses that were drastically reduced by the Second World War: some disappeared completely, barely remembered by history.

The second golden age arrived in the 1950s, with the major influence of Christian Dior and his New Look, which redefined the codes of elegance and enabled Paris to hold on to its status as the fashion capital of the world after the war. Interestingly, this period was also marked by the emergence of ready-to-wear.

Finally, the 1990s marked a third, very different, golden age. Couture moved away from the everyday to the spectacular. Shows took on theatrical proportions, and the silhouettes, often grandiose, emancipated themselves from the idea of wearability. Before the 1990s, even the most exceptional Haute Couture creations, although reserved for an elite, were still designed to be worn. But from this period onwards, Haute Couture became a laboratory of ideas, where the artistic dimension took precedence over practical use.

One element seems interesting for understanding post-war Haute Couture: it triumphed but had to compete with the new ready-to-wear system, which replaced what used to be called confection. How did Haute Couture react to this shift?

In fact, what saved Haute Couture after the war was its adaptation to ready-to-wear. From the ’50s and ’60s, fashion houses began to launch their own lines, with Dior and Givenchy among the forerunners. The ’50s are generally remembered as the age of success for Christian Dior, Hubert de Givenchy and Cristobal Balenciaga. Later, the name Yves Saint Laurent would also become synonymous with Parisian Haute Couture. But the perception of this story needs to be adjusted, because in reality, many fashion houses disappeared, unable to survive without ready-to-wear, which provided a source of income. You could say that ready-to-wear kept alive a system that, on its own, was no longer making enough money.

It's also important to point out that many houses have disappeared, and for almost two decades there have been attempts to revive them. I'm thinking of several attempts around Paul Poiret or, more recently, Madeleine Vionnet?

It's a difficult exercise, but there have also been successes. Schiaparelli is a good example. Under the direction of Daniel Roseberry, the house has reinvented itself while remaining faithful to the heritage of Elsa Schiaparelli, who was already avant-garde in the 1930s.

She was one of the first to transform the fashion show into a spectacle. At the time, when the norm was the private couture salon, she organised shows in unexpected places, like a circus. She was already combining the dreamlike with exceptional craftsmanship, couture that makes you dream, while celebrating the details and the work of the ateliers.

Today, Schiaparelli remains spectacular, but in a different way. The codes have been reinterpreted for a contemporary era, with a strong emphasis on craftsmanship and an impressive theatricality. This kind of successful relaunch is rare, because you have to strike a balance between respect for heritage and a modern vision capable of captivating a new audience.

You spoke of a third golden age for Haute Couture in the 1990s. Can you tell us more about this?

This period marked a major turning point, and 1997 was a pivotal year. As Alexandre Samson's 1997 exhibition, Fashion Big Bang, at the Palais Galliera demonstrated, it was a period when new English designers – John Galliano and Alexander McQueen – were breathing new life into the Parisian scene, just as haute couture was becoming passé. It was also the year that Thierry Mugler and Jean-Paul Gaultier became couturiers, a key moment when, for the first time, the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture took a step backwards in its regulations.

Traditionally, only designers who met very strict criteria, such as producing only handcrafted pieces in dedicated workshops, could claim this status. However, Mugler and Gaultier had mixed collections: some of their work was couture, but not all. Their admissions reflected a desire to revive interest in Haute Couture, thanks in large part to their spectacular shows, which were among the most impressive of the era.

Traditionally, only designers who met very strict criteria, such as producing only handcrafted pieces in dedicated workshops, could claim this status. However, Mugler and Gaultier had mixed collections: some of their work was couture, but not all. Their admissions reflected a desire to revive interest in Haute Couture, thanks in large part to their spectacular shows, which were among the most impressive of the era.

As for Alexander McQueen at Givenchy and John Galliano at Dior, they too transformed the couture show into a total spectacle. With these four names, Haute Couture emancipated itself from the codes of wearability. The highlight? Mugler's Chimère, presented on 10 July 1997 as a fashion show lasting more than 50 minutes with an organ playing in the background and smoke billowing out. The dress is an articulation of material and colour, telling the story of this mythological creature from Ancient Greece, made up of various animals. How do you find the opportunity to wear something as theatrical as the Chimera? We can sum up and say that the Third Golden Age brings together creators who have reinjected dream and extravagance into a system that has run out of steam, while redefining the boundaries between craft and spectacle.

With Julien Sanders, you devoted the second issue of your magazine Griffé to Thierry Mugler. What did you learn about his relationship with Haute Couture?

Thierry Mugler was all about spectacle. Before 1997, his shows were already ultra-scenographic, mixing ready-to-wear with exceptional pieces. To put together the issue we spoke to Didier Grumbach, who was President of the Federation and CEO of Mugler, and who explained that Mugler first entered the Haute Couture Week Official Calendar as a Guest in 1993 with his Ritz collection in a bid to give the scene a new edge. But it wasn't until 1997 that he became a permanent guest. But this change created tensions: some traditional houses, already economically fragile, thought it unfair to see more free-spirited houses join the Official Calendar. Several articles from the period illustrate this.

For Mugler, the Haute Couture label was above all a pretext for pushing back the boundaries of clothing.

Each couture piece was designed for the moment of the show, and if he didn't sell them, it didn't matter. This led to ever more spectacular creations, culminating in the apotheosis of Chimère. This taste for the stage continued after he left his brand, which was bought by Clarins in 2003, designing for tours such as Beyoncé's in 2009.In short, for Mugler, haute couture was a space of absolute artistic freedom, much more than a business model...

What are the latest Haute Couture shows that you think will go down in history?

It's always hard to say, but a year ago, Maison Margiela Artisanal by John Galliano created a huge buzz.

It marked a desire to reconnect with the “third golden age” of Couture, that of 1997, when Galliano helped redefine the spectacle of Couture by making it desirable once again. Today, we are seeing a return of interest in these shows. We also owe this revival to Demna with Balenciaga. He reminded us that Couture could tell powerful stories, while updating its codes. He plays on references to classic Couture, and Cristobal Balenciaga's formula, which he modernises and applies to everyday garments: hoodies and trainers are made noble by impeccable cuts. It's also worth noting the strong scenography of the Couture shows, where the staging codes of the second golden age remain visible, but give way to new collections that are far from past. These shows mark a new idea of Couture: a laboratory of stories and symbols, fusing the everyday with the exceptional. Daniel Roseberry for Schiaparelli embodies another path of this contemporary brilliance of Couture.

Might we arrive at a fourth golden age of Haute Couture?

We may be experiencing a new turning point, and this season's arrival of Kevin Germanier in haute couture is a good example. It's not so often that we see new names on this calendar, which evolves much more slowly than ready-to-wear. Germanier is interesting because he is refocusing couture on craftsmanship and innovation, thanks in particular to his use of upcycling. It's not totally new, but it's rare.

Jean-Paul Gaultier explored this in his spring 2002 haute couture collection, with his famous corset made from ties found at flea markets. It was already a powerful gesture, showing that recycling could be profoundly couture: each piece is unique, because each material is unique from the start. Martin Margiela was, of course, a proponent of reuse, redesigning garments from used pieces whose traces were often visible and staged. His inclusion in the Other Couture calendar in 2008 spoke volumes. These practices prove that luxury can be born from what already exists, without losing any of its savoir-faire.

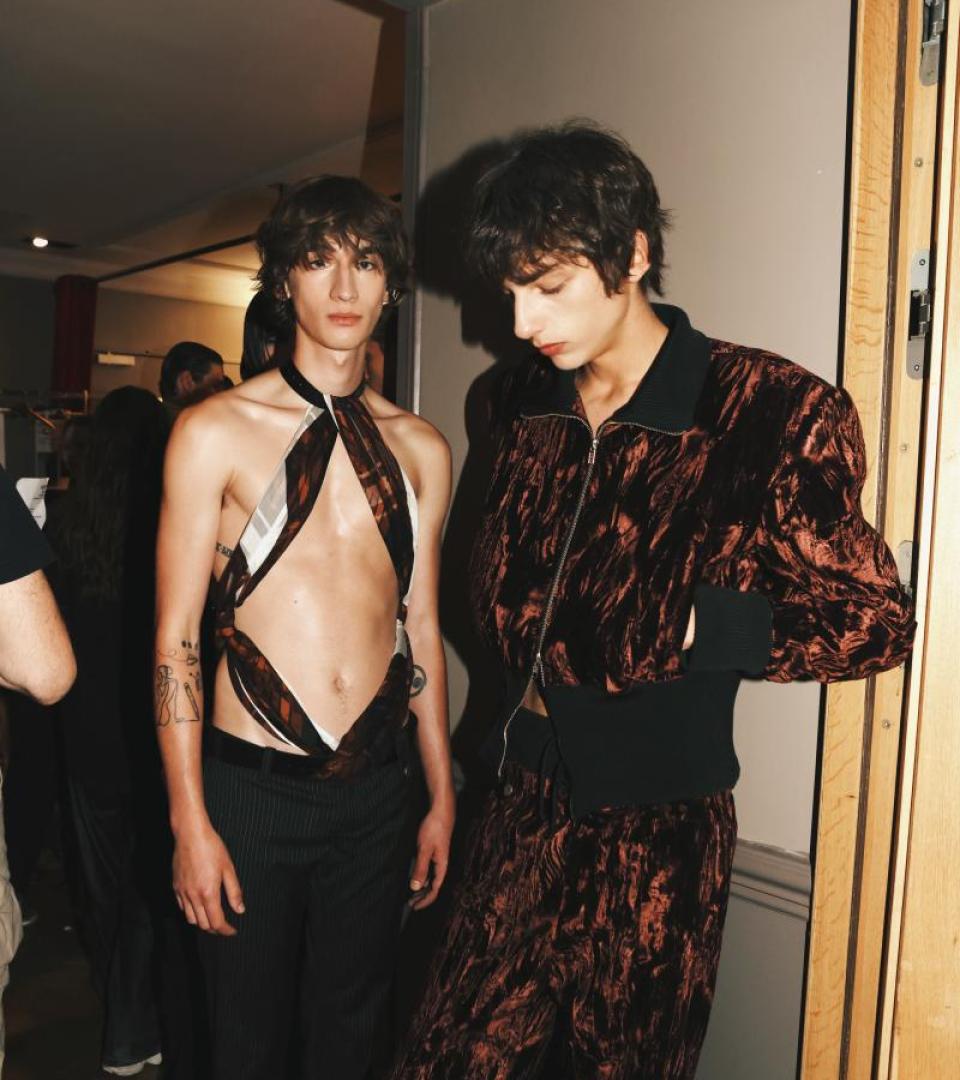

Germanier is part of this continuity, but also brings it up to date: he embodies a generation that is rethinking fashion by combining Couture, inclusivity and sustainability. He is a worthy representative of this new Parisian scene, alongside designers such as Jeanne Friot and Louis Gabriel Nouchi, who were also present at the Olympic Games, and who take a critical and committed look at the challenges facing contemporary fashion.

This interview has been lightly edited.