Musée d’Orsay: Whistler Exhibition

Three portraits by James Abbott McNeill Whistler that are among the main attractions of the Frick Collection – currently under renovation – have travelled for the first time in more than a century from New York to the Musée d’Orsay. The exhibition’s curator, Paul Perrin, sheds light on how the painter was advancing ideas of composition and colour while playing a key role in the fashion his subjects wore.

Beyond Whistler’s Mother, which is among Whistler’s most recognisable works, the Musée d’Orsay’s collection doesn’t include many American artists from the second half of the 19th century.

We don’t have many American artists in the Musée d’Orsay, but Whistler was probably among the first artists the French museums began collecting in the late 19th century. In our collection, we have the masterpiece, Whistler’s Mother, which is an early portrait from 1871 and these Frick Collection portraits allow us to see, from this starting point, where he goes.

The monochrome aspect of these paintings – right down to the wardrobe – seems so radical. What was Whistler motivation for blending fashion into the overall composition?

Whistler had the idea that every part of the composition is important – not only the centre, not only the foreground, and not only the human figure. He wants the whole painting to be flat and unified. The figure is fusing with everything around it. The less colour there is, the more you have this impression of a whole harmony of colours and shapes. That is why he moves towards subtle harmonies that are more and more sober, minimalist. Everything is a kind of blur around the shapes. And you don’t really see the details, especially in the black portraits. To him, the general silhouette is more important. Whistler didn’t want to go too deep in description because his art is about suggestion.

For Symphony in Flesh Colour and Pink: Portrait of Mrs. Frances Leyland, Whistler wanted her to wear a dress with a flowing silhouette rather than a corseted style, still more typical at the time. How does he use fashion to reveal a shift in aesthetics and conventions?

I think Whistler’s art is about the rejection of the Victorian artistic conventions but also the French bourgeois art conventions. For him, every aspect of life should be invested by art, especially in England where he and another group of artists like the Pre-Raphaelites and the Aesthetics find contemporary Britain ugly, industrialised. They want more freedom, liberty; and they want their art to be free of the conventions. This is reflected in the way they dress in a more artistic way. They are proposing a new fashion and a new beauty for women – more sensual, more fluid. There are also new influences in fashion for these avant-garde artists who were looking toward two directions: firstly, the French 18th century, as you can see the portrait of Frances Leyland shows her in a tea gown with a Watteau back. There is also some suggestion of the kimono with its long sleeves, and such textiles were very in style at the time as artists discovered the art of Japan.

Whistler was known to be a dandy and to put effort into his own presentation.

I think he was really a perfect dandy of his time. He was really aware of how he dressed. We have accounts from other people at the time who noted he was very well attired. He dressed with this idea of leisure class, and he had a very witty spirit. The way he presented himself and talked about art with humour was all part of his persona. He was a new type of artist and fashion was part of this.

Arrangement in Brown and Black: Portrait of Miss Rosa Corder shows a woman in black equestrian dress against a black background. What would Whistler be signalling here?

The idea of her being more active – she is in a day outfit to wear outside, It’s also a departure from a night scene or the feeling of a salon. This was dress for going out, for walking, for sport. It was also something that was new of the time, a sign of the evolution in women’s fashion because women were more and more active in the public space.

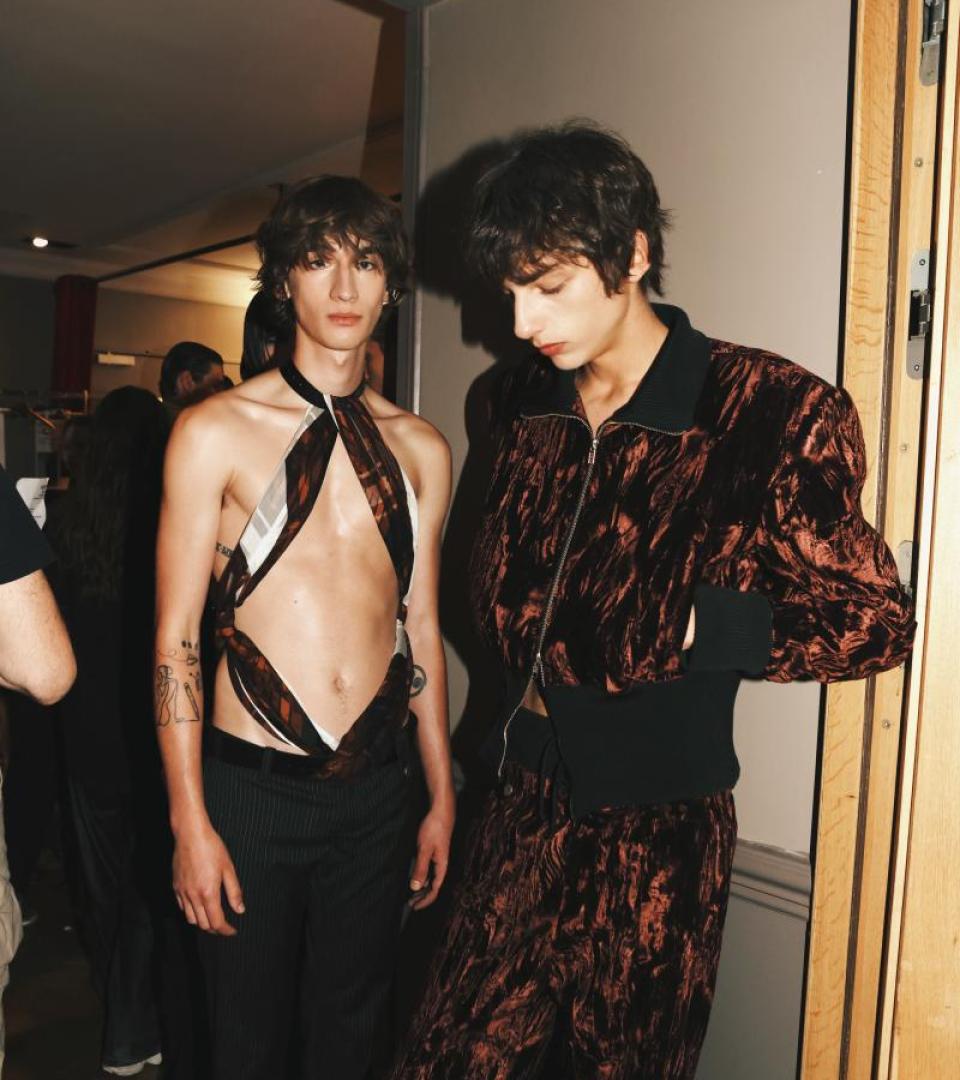

Another interesting detail is the chinchilla stole on the arm of Count Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac which belonged to Countess Greffulhe, the prominent Parisian socialite and patron.

It is an interesting detail. There is some subversion of the genders. Because this is a more feminine accessory, and it gives the portrait a slightly more feminine touch. But this corresponds with Montesquiou’s sophisticated and more effeminate personality. Whistler really captured that.

James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) Masterpieces from The Frick Collection, New York continues at the Musée d’Orsay until May 8th, 2022.